Smart cities promise efficiency, sustainability, and improved quality of life through artificial intelligence integration. Yet beneath this technological utopia lies a complex web of ethical challenges that demand urgent attention and thoughtful navigation.

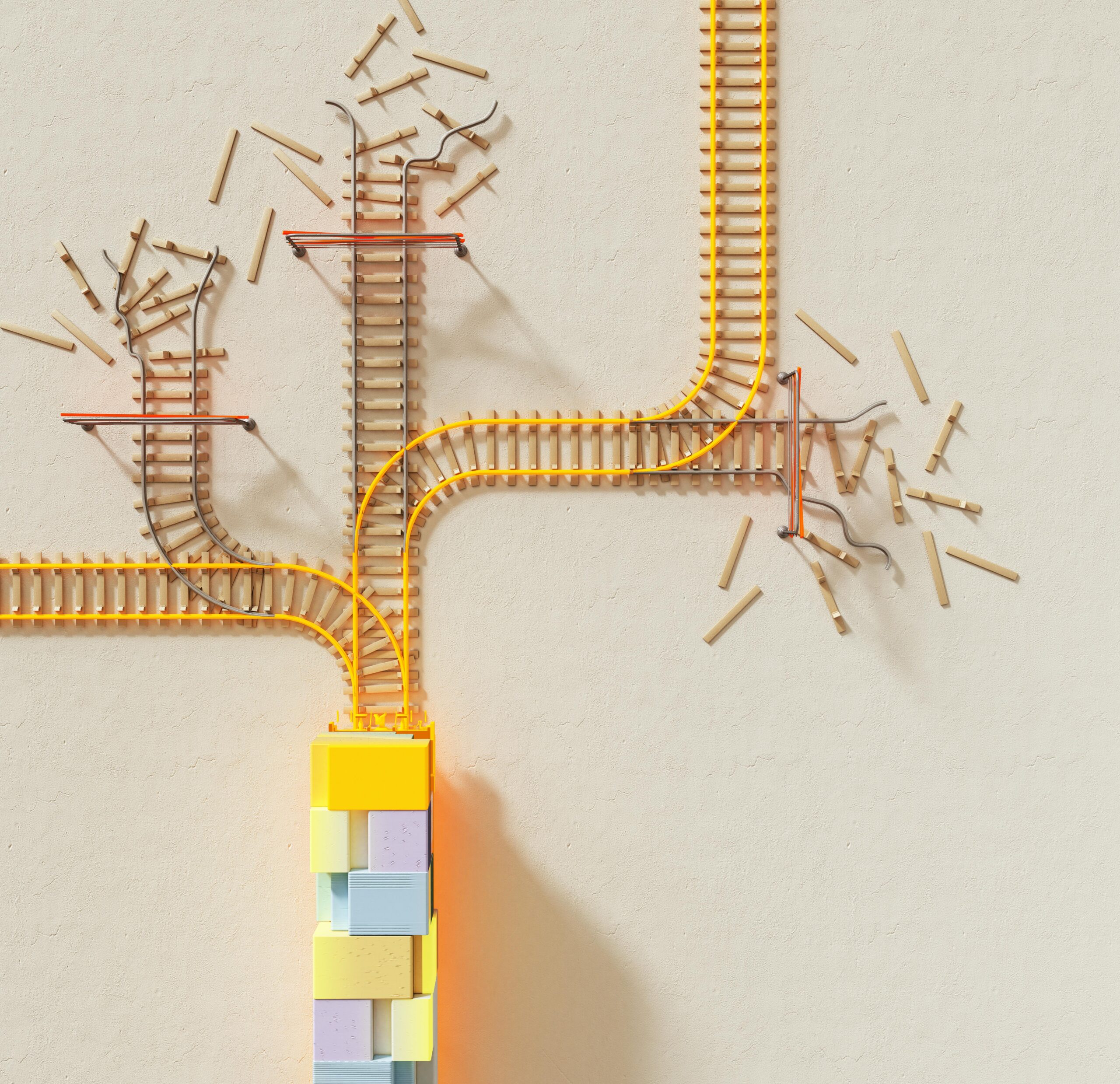

As urban centers worldwide embrace AI-driven solutions, from traffic management systems to predictive policing algorithms, the potential for bias and unintended consequences grows exponentially. The intersection of technology, governance, and human rights creates a labyrinth of ethical considerations that city planners, policymakers, and citizens must navigate together to build truly inclusive urban environments.

🏙️ The Promise and Peril of AI in Urban Infrastructure

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized how cities operate, offering unprecedented capabilities to optimize resources, predict maintenance needs, and respond to citizen requirements in real-time. Smart traffic systems reduce congestion, intelligent waste management decreases environmental impact, and predictive analytics help allocate public services more effectively.

However, these technological advances carry inherent risks. AI systems learn from historical data, which often reflects existing societal biases and inequalities. When these biased patterns are encoded into decision-making algorithms, they can perpetuate and amplify discrimination, creating digital divides that mirror or worsen traditional social disparities.

The challenge lies not in abandoning AI technology but in developing frameworks that harness its potential while actively mitigating harmful outcomes. This requires understanding where bias enters the system and implementing safeguards throughout the entire lifecycle of AI deployment.

Understanding the Sources of Algorithmic Bias

Bias in AI-driven smart city systems emerges from multiple sources, each requiring distinct mitigation strategies. Data bias represents the most common culprit, occurring when training datasets fail to represent diverse populations adequately or contain historical prejudices.

Historical Data Reflects Historical Inequities

When AI systems learn from past policing records, housing patterns, or loan approval decisions, they inevitably absorb the discrimination embedded in those historical practices. A predictive policing algorithm trained on biased arrest data will direct more resources to already over-policed communities, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of increased surveillance and enforcement.

Similarly, algorithms determining resource allocation for public services may perpetuate underinvestment in marginalized neighborhoods if they rely solely on historical spending patterns that reflected discriminatory practices.

Design Bias and Technical Limitations

Engineers and data scientists, despite best intentions, bring their own perspectives and blind spots to AI development. Homogeneous development teams may fail to anticipate how their systems will impact diverse user groups, leading to functionality that works well for some populations while failing or harming others.

Facial recognition technology, for instance, has demonstrated significantly higher error rates for people with darker skin tones and women, leading to misidentification issues with serious consequences when deployed in security or law enforcement contexts.

Privacy Concerns in the Connected Urban Environment 🔒

Smart cities generate massive amounts of data through sensors, cameras, connected devices, and citizen interactions with digital services. This data collection raises fundamental questions about surveillance, consent, and the appropriate balance between public benefit and individual privacy.

Citizens often lack transparency regarding what data is collected, how it’s used, who has access, and how long it’s retained. The absence of clear data governance frameworks creates opportunities for mission creep, where data collected for one purpose gradually expands to serve other functions without explicit consent or public debate.

The Surveillance Society Question

When does a smart city cross the line into becoming a surveillance city? This question becomes increasingly urgent as AI-powered facial recognition, gait analysis, and behavioral prediction technologies become more sophisticated and ubiquitous.

Cities like London and Beijing have deployed extensive camera networks with facial recognition capabilities, raising concerns about chilling effects on freedom of expression, assembly, and movement. The normalization of constant monitoring fundamentally alters the relationship between citizens and their government, potentially eroding trust and democratic participation.

Equity and Access in Digital Urban Services

The digital divide represents another critical ethical dimension of AI-driven smart cities. As essential services increasingly migrate to digital platforms requiring smartphones, internet connectivity, and digital literacy, populations lacking these resources face exclusion from civic participation and access to services.

Elderly residents, low-income communities, people with disabilities, and those in rural or underserved areas may find themselves unable to access transportation apps, digital permit systems, or online public services that replace traditional alternatives.

Building Inclusive Digital Infrastructure

Ethical smart city development requires intentional design for universal access. This means maintaining non-digital service alternatives, ensuring affordable internet access, providing digital literacy programs, and actively engaging marginalized communities in technology deployment decisions.

Copenhagen and Amsterdam have pioneered participatory approaches, involving diverse citizen groups in smart city planning processes to ensure technology serves broad public interests rather than narrow commercial or administrative efficiency goals.

Accountability and Transparency in Automated Decision-Making ⚖️

As AI systems assume greater responsibility for consequential decisions affecting housing, employment, credit, and public safety, establishing clear accountability mechanisms becomes essential. When an algorithm denies a permit application, flags someone for additional security screening, or allocates fewer resources to a neighborhood, citizens deserve to understand why and have meaningful recourse.

The “black box” nature of many machine learning systems complicates this requirement. Complex neural networks may produce accurate predictions without providing human-understandable explanations for their decisions, creating tension between system performance and democratic accountability.

Explainable AI and Right to Explanation

Recent regulatory frameworks, including the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, have begun establishing rights to explanation for automated decisions. However, implementing these rights in practice remains challenging, particularly for sophisticated AI systems.

Smart cities must prioritize transparency by documenting AI system purposes, data sources, decision-making logic, accuracy rates, and known limitations. Public algorithms registries, where cities catalog their automated systems and their uses, represent one promising approach to enhanced transparency.

Environmental Justice and Algorithmic Resource Allocation

AI optimization in smart cities often focuses on aggregate efficiency metrics like reduced energy consumption or improved traffic flow. However, these system-level improvements may mask unequal distributions of benefits and harms across different communities.

An AI traffic management system that optimizes for overall vehicle throughput might route heavy truck traffic through low-income residential areas, improving efficiency for the majority while concentrating air pollution and noise in vulnerable neighborhoods.

Programming Fairness Into Optimization Algorithms

Addressing these equity concerns requires explicitly incorporating fairness criteria into AI objective functions. Rather than optimizing purely for efficiency, algorithms must balance multiple values including equitable distribution of benefits, minimizing harm to vulnerable populations, and environmental justice considerations.

This technical challenge also represents a profound political question: who decides what constitutes “fair” distribution, and through what democratic processes are those decisions made?

Governance Frameworks for Ethical AI Deployment 📋

Navigating the ethical maze of AI-driven smart cities requires robust governance frameworks that establish clear principles, processes, and oversight mechanisms. Several cities and international organizations have developed guidelines and standards worth examining.

- Barcelona’s Digital City Plan emphasizes technological sovereignty, data commons, and citizen empowerment

- Toronto’s cancelled Sidewalk Labs project highlighted the importance of meaningful public consultation and data governance clarity

- The IEEE’s Ethically Aligned Design framework provides technical standards for prioritizing human wellbeing in autonomous systems

- The EU’s proposed AI Act establishes risk-based regulatory requirements for high-stakes AI applications

Multi-Stakeholder Participation and Oversight

Effective governance requires ongoing participation from diverse stakeholders including technical experts, ethicists, community advocates, affected populations, and policymakers. Ethics review boards, citizen assemblies, and participatory budgeting processes can provide mechanisms for democratic input into smart city technology decisions.

Independent auditing of AI systems offers another crucial accountability mechanism. Third-party auditors can assess systems for bias, accuracy, privacy compliance, and adherence to stated purposes, providing public assurance and identifying issues before they cause widespread harm.

Building Trust Through Ethical AI Practices 🤝

Public trust represents the foundation upon which successful smart cities must be built. Without citizen confidence that technology serves their interests and respects their rights, even technically sophisticated systems will fail to achieve their potential or face resistance and rejection.

Building this trust requires consistent demonstration of ethical principles through concrete practices. Cities must move beyond aspirational statements to implement verifiable safeguards, respond transparently when systems fail, and empower citizens with genuine control over their data and meaningful input into technology governance.

Privacy-Preserving Technologies and Data Minimization

Technical approaches like differential privacy, federated learning, and edge computing enable smart city functionality while reducing privacy risks. These techniques allow AI systems to gain insights from data patterns without requiring centralized collection of personal information.

Data minimization principles should guide collection decisions, gathering only information necessary for specific, articulated purposes and deleting it when no longer needed. This approach contrasts with prevalent “collect everything” mentalities that create massive honeypots of personal information vulnerable to breaches and misuse.

The Path Forward: Recommendations for Ethical Smart Cities

Successfully navigating the ethical challenges of AI-driven urban development requires sustained commitment across multiple dimensions. Technical solutions alone cannot address fundamentally social and political questions about values, power, and justice.

Prioritize Human Rights and Dignity

Every technology deployment decision should begin with human rights impact assessment, considering how systems might affect privacy, equality, freedom of expression, and other fundamental rights. When conflicts arise between efficiency and rights protection, cities must prioritize human dignity.

Embed Equity From the Beginning

Rather than treating equity as an afterthought or add-on feature, fairness considerations must shape system design from inception. This includes diversifying development teams, engaging affected communities as co-designers, and establishing equity metrics alongside efficiency measures.

Maintain Human Oversight and Decision-Making Authority

AI should augment rather than replace human judgment, particularly for consequential decisions affecting individual rights and opportunities. Maintaining humans in the loop preserves accountability, allows for contextual considerations that algorithms miss, and provides avenues for appeal and correction.

Invest in Digital Literacy and Inclusion

Smart cities must actively work to bridge digital divides through investments in infrastructure, education, and accessible design. Technology should expand rather than restrict civic participation and access to public goods.

Establish Ongoing Evaluation and Adaptation Mechanisms

Ethical governance is not a one-time implementation but an ongoing process. Regular audits, impact assessments, and public feedback mechanisms allow cities to identify emerging issues and adapt systems as technologies and social contexts evolve.

Learning From Mistakes and Near-Misses 🎯

The relatively brief history of smart cities already offers valuable lessons from both successes and failures. Toronto’s Sidewalk Labs controversy demonstrated the importance of clarifying data governance and decision-making authority before deployment. San Diego’s smart streetlight program faced backlash when sensors initially deployed for traffic and environmental monitoring were accessed by police without public knowledge or consent.

These examples underscore the importance of transparency, clear purpose limitation, and robust stakeholder engagement throughout the technology lifecycle. They also highlight how quickly public trust can erode when systems operate contrary to stated purposes or public expectations.

Shaping Technology That Serves Humanity

The ethical challenges of AI-driven smart cities ultimately reflect broader questions about what kind of future we want to create and who gets to decide. Technology is not neutral or inevitable; it embodies the values, priorities, and power structures of those who design and deploy it.

By centering ethics, equity, and human rights in smart city development, we can harness AI’s potential to create more livable, sustainable, and just urban environments. This requires vigilance, ongoing effort, and willingness to prioritize human flourishing over efficiency metrics or commercial interests.

The ethical maze is navigable, but only through collective commitment to democratic governance, transparent operations, accountable systems, and genuine respect for human dignity. The cities we build today will shape the lives of billions of people for generations to come, making this challenge one we cannot afford to navigate carelessly.

As AI capabilities continue advancing and urban populations grow, the stakes of these ethical decisions will only increase. By establishing strong foundations now, embedding fairness and accountability into our technological infrastructure, we can ensure that smart cities truly serve all their residents rather than optimizing for narrow interests at the expense of broader human values.

Toni Santos is a technology and sustainability researcher exploring how artificial intelligence and design can build smarter, greener cities. Through his work, Toni examines how digital innovation enhances urban life, architecture, and mobility. Fascinated by the fusion of technology and human environments, he studies how intelligent systems can promote balance between progress, ethics, and ecology. Blending urban design, AI research, and environmental consciousness, Toni writes about the transformation of cities through innovation with purpose. His work is a tribute to: The evolution of cities through intelligence and design The harmony between technology and sustainability The vision of a connected, equitable urban future Whether you are passionate about smart cities, green architecture, or AI-driven innovation, Toni invites you to explore the cities of tomorrow — one idea, one design, one connection at a time.